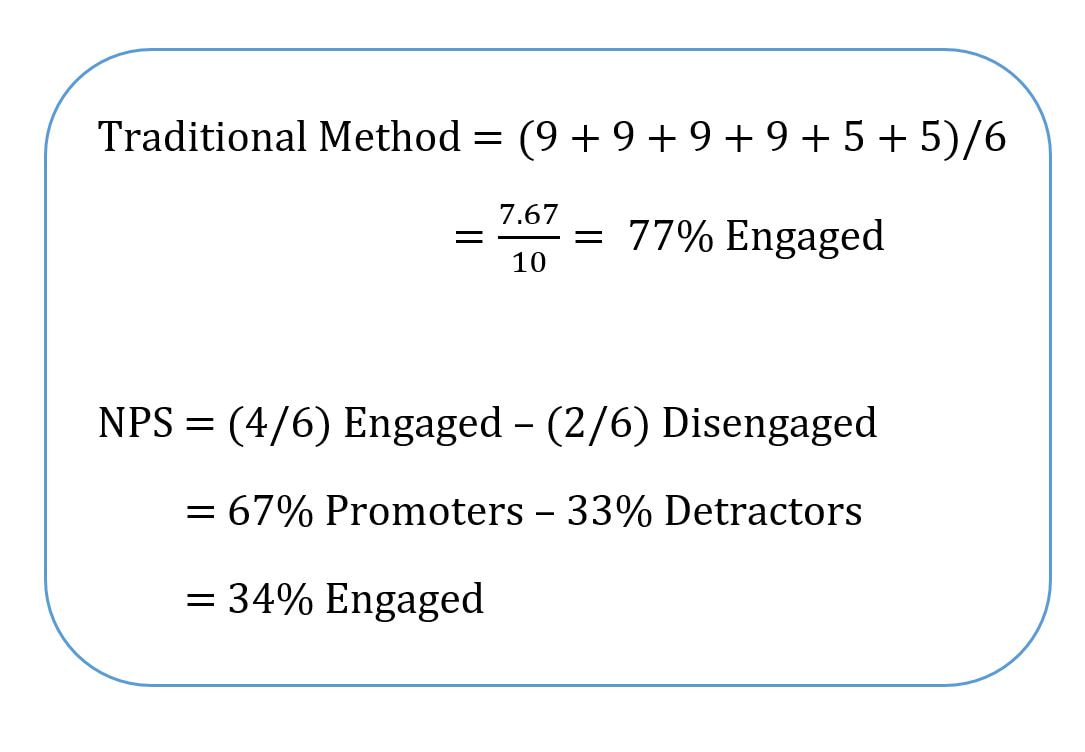

Employees are so vital to our bottom line. Increased efforts and efficiencies can help increase profit by reducing expenses. This got me thinking, if employees impact our profit so much, why don't we put similar efforts into employees as we do when we chase revenues? In other words, why don't we chase employees the same way we chase customers? One way we can change our mindset is by using metrics from customer service--particularly, Net Promoter Scores. Instead of taking an overall average of percentage of customers that like your company, Net Promoter Scores subtract any detractors from your promoters.

Seeing a 34%, I would want to delve into these results. Let's continue down the customer service path and examine what this score means in comparison to 'market segments'. For example, what happens if we find males are the 4 engaged and women are the 2 disengaged? Or perhaps baby boomers are engaged but the 2 millennials are disengaged? In the traditional approach, we may have not even intervened. Now we have a completely different intervention around diversity & inclusion or discrimination.

Implementation Before you jump into converting your engagement calculations over, test this out with some of your people leader's engagement scores. Does it give you any surprises? Or does it tell you the story you already knew but didn't have evidence for? Use this to build your business case. Next, determine how you may action this change? And how many resources do you have to do it? If we are still considering employees like customers, how big is your 'internal engagement team' compared to your sales team? Effective implementation will involve a large team and/or user-friendly software for administration and analytics. Additionally, either your people leaders or Human Resources Business Partners need to have the skills and knowledge to be able to access, analyze, and take action based on these results. How mature is your organization to do this? Additional Lessons from Customer Service In addition to an engagement NPS, there are other potential metrics from customer service that may be important to consider using. For example, we set sales targets, but are you setting engagement targets for your people leaders? What other other metrics we could use? How about:

What other metrics can you think of?

0 Comments

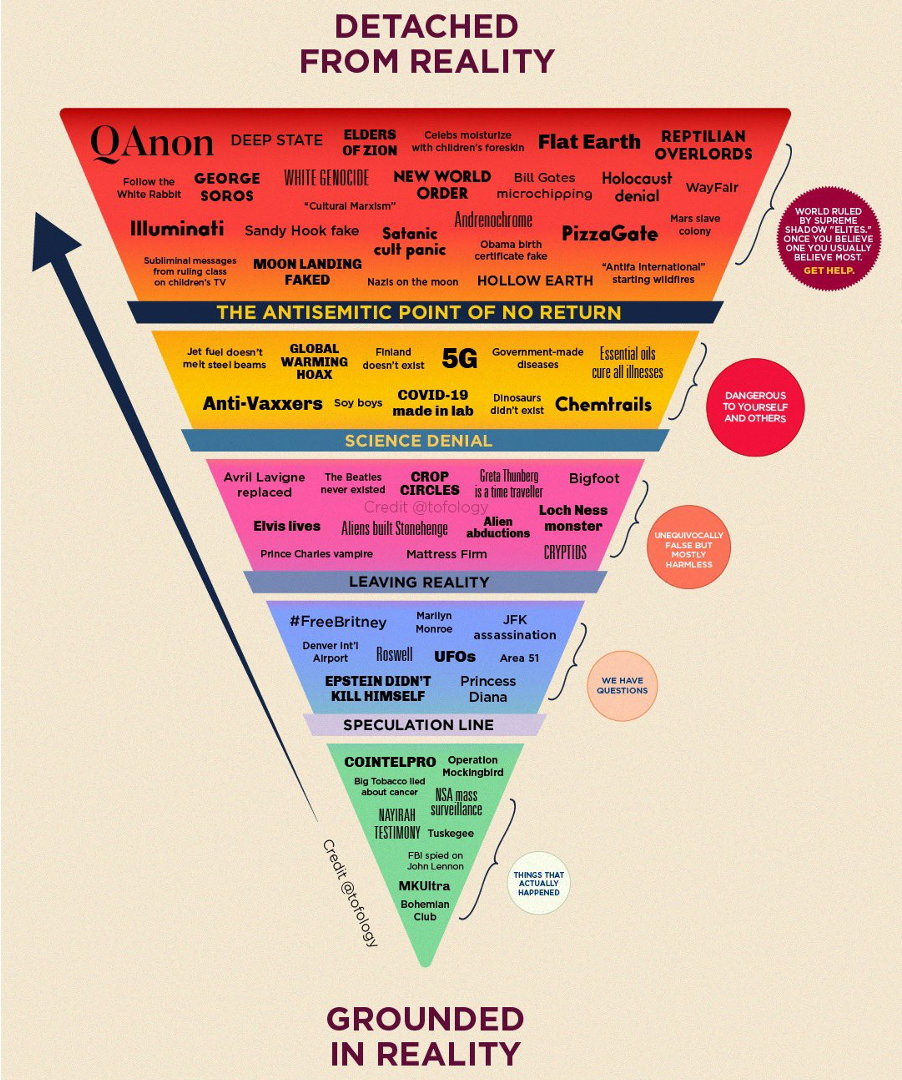

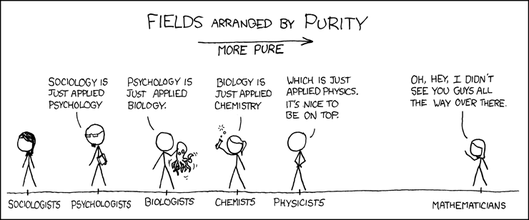

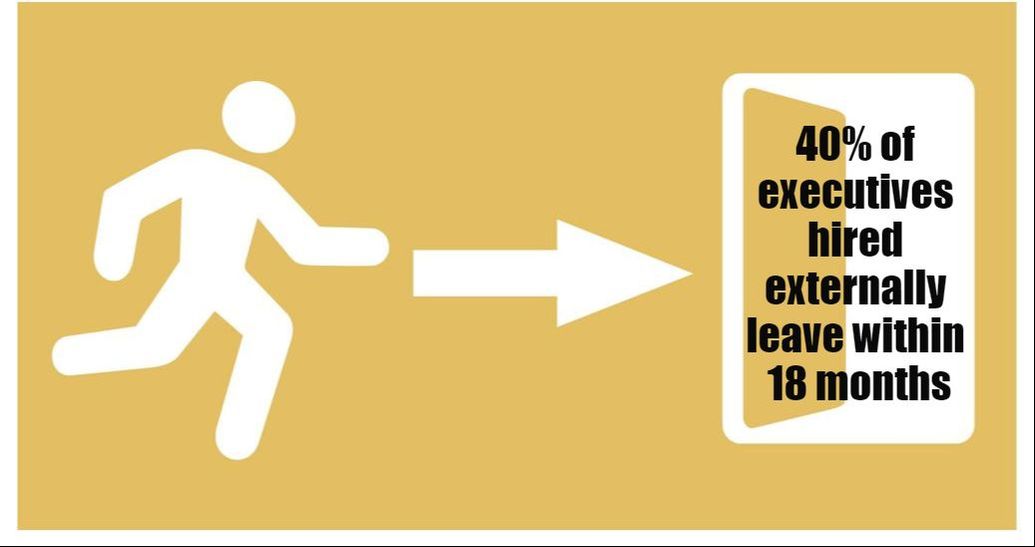

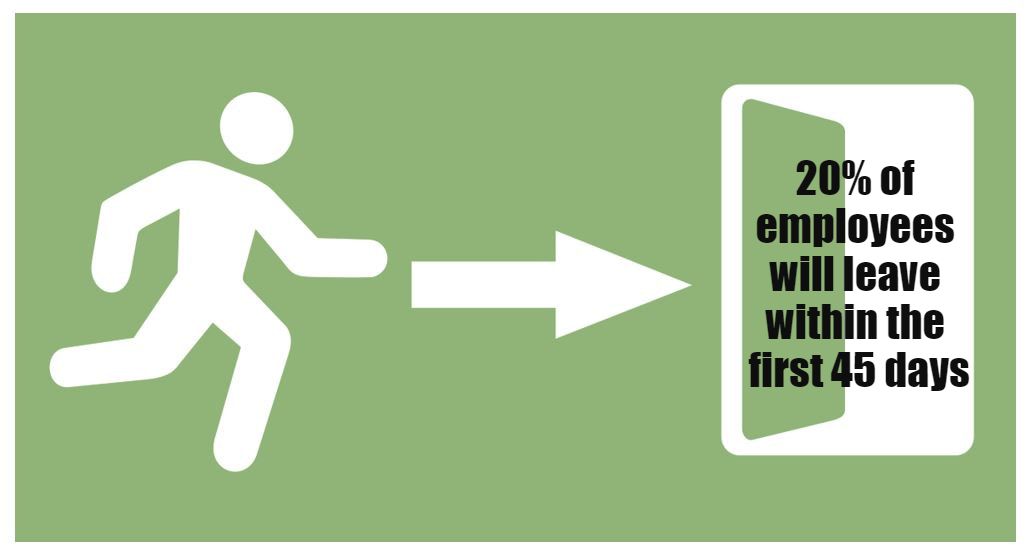

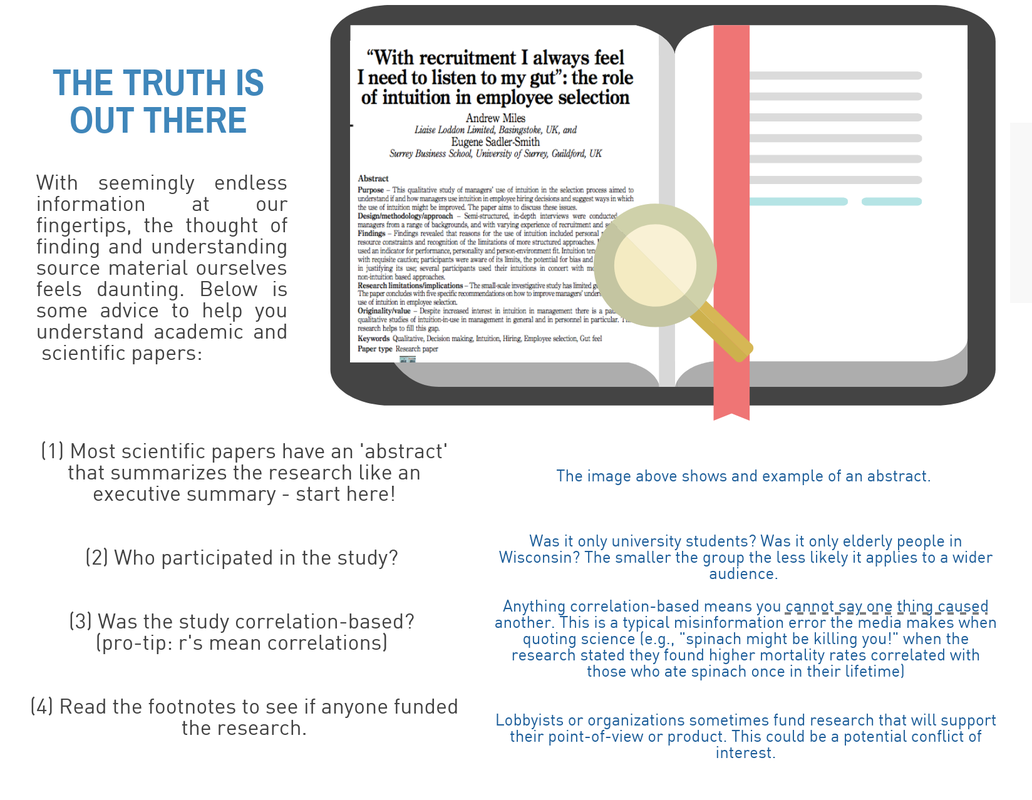

Let's start off and imagine you are a chemist and you study hydrogen. You conduct experiments on hydrogen and make conclusions about what you observed when you added or changed things while testing hydrogen. You publish this information in science journals such as Nature or Science. Now everyone in the world can make the same assumptions about hydrogen. Now imagine in the same scenario that when you study hydrogen from different suppliers, each supplier provides you with slightly different measurements of hydrogen. Hmm, I suppose you could work with that, you can control from some differences or tell people which supplier you used in your experiments so they can use your findings if it's the same supplier or type of hydrogen they are using. Now let's take this one step further...not only is the hydrogen different from the different suppliers, but each time you examine the same hydrogen sample it gives you different results. What the heck is going on? How do you make sweeping generalizations to other samples of hydrogen? How can we even progress our knowledge in this field? How can we make the non-scientific community comfortable with our findings? What I am trying to demonstrate is what psychology and other social sciences are faced with. Think of the hydrogen as 'people'. Now, think of the suppliers as different countries, genders, organizations, whatever. We think we get a handle of information and then the rug gets pulled from under us because we find some other variable or attribute changes how "people" are country-to-country, or from male-to-female, etc. Unlike the chemist who can take the sample of hydrogen and make generalizations to hydrogen everywhere, social scientists can't necessarily do that. Therefore, social scientists use statistics to take a sub-sample of the population and try and generalize it to the whole. That is, we try to ensure we include people from as wide of variety of life that we can, within reason. When we talked about getting different results each time, this is another 'fun' caveat when studying people. I could give you the same personality test two days apart and I wouldn't get the same answers. I would probably get 95% of the same responses, but would almost never be 100% the same. We then have to create rigorous testing parameters to make sure any test or assessment is valid and reliable. However, with everyone from Facebook to Buzzfeed creating a 'quiz' on "what is your type" we start to blur the lines of who is knowledgeable in creating an assessment. Therefore, sometimes us social scientists feel we have the odds stacked against us. It doesn't help that other scientists such as physicians and chemists call us "soft". Additionally, once the media gets a hold of our studies, information gets watered down or one one day you hear "this is good for you" then the next "this is bad for you", or "absence makes the heart grow fonder" versus "out of sight, out of mind". Then, you lose trust in us. I'm writing about this to reassure you and help provide you with tools to how to trust social scientists again. For us social scientists, we are responsible to ensure rigourous testing conditions and informing you on who we studied and what our limitations are. For example, the limitations section may discuss how generalizable our findings are. We talk about whether we only studied university students or only one particular organization and how that may impact the results. These are vital pieces that can get omitted by media reports. Now the study that should have only been applied to young adults gets applied to everyone and it isn't true. Not only is the media responsible to find that information, but you are too. Dig deeper before you Retweet or Like that headline. Remember that, contrary to the Westworld 2 season finale, us humans aren't as simple as a book's worth of code. Science needs people to be critical thinkers on both the giving and receiving ends of the information.  How we fail our new hires We put so much time and resources into hiring employees—sourcing, assessing, interviewing, negotiating—that we are exhausted by the time their start date rolls around. We justify that it's okay and the “sink or swim” is a good initiation – I mean we had to do it ourselves, right?

So how do we get out new hires to thrive? Let's start with Day 1. Even better, let's start with Day -1. Have new hires complete paperwork so that their benefits and payroll will be set up beforehand. Also create an open line of communication so they can ask questions before their start date. Finally, welcome them on behalf of the organization, hiring manager, and/or team. So then what is lined up on Day 1 for the employee? It should be more than just orientation. How boring is it to sit in front of a screen and click through modules of company propaganda? Why not kick off with an informal coffee/breakfast with the hiring manager to discuss what to expect in the coming months? This is also a great time to provide resources to the employee such as their job description, company information, strategic objectives, industry knowledge, and key points of contact. Perhaps then the employee meets with their buddy. This buddy is a champion of the organization and not only gives a facility and safety tour, but starts providing tips about the unwritten rules. The Talent Team could then meet with the employee to discuss any assessment results they went through in the recruitment phase. Understanding their assessment begins to help them understand their strengths and their possible derailers within the context of the team and organization. Next, the employee goes for an informal lunch with their team, they start placing names to faces, asking and fielding questions. The afternoon could then be filled with module training, paperwork, and reflection time to get them situated, followed by an end-of-day quick check-in with their manager to answer any immediate questions and outline the remainder of the week. How would you feel after that kind of first day? The purpose of onboarding is about opening dialogue and establishing fit. The employee needs to see how their role contributes to the organization and they also need to see how their own values and style fits within the team and culture. Building this buy-in creates engagement. Understandably engagement cannot be built in a day, a week, or even 100 days. It's an ongoing process and takes at least 6 months, if not a year. However, the results are worth it. With effective onboarding, 69% of employees are staying with the company for at least 3 years. This greatly reduces recruitment costs--money which can now be funneled into new onboarding initiatives, like enhanced technology and training. Good onboarding practices also increase performance outcomes such as goal attainment, customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and revenue. The 'sink or swim' approach is starting to look pretty bad now isn't it? So let's incorporate some best practice into our onboarding (there are even practices that cost little to no money) and let's have our employees and our organizations thrive! After investing into my consulting business full-time, I am fortunate to have flexibility, autonomy, and days where I stay at home working in my housecoat. However, it wasn’t very long ago I was working 11-hours days, answering emails on vacation, and taking my dual monitor home on long weekends.  Working is no longer clocking in at 9:00 am and clocking out at 5:00 pm. Work is now physically or virtually arriving between 7:00am and 10:00am and leaving between 3:00pm and 6:00pm, all while juggling personal phone calls, work e-mails, doctor’s appointments, social media, conference calls, news reports, in-person meetings, the list goes on. Once home, the work phone still buzzes from colleagues around the world or from people burning the midnight oil. There is no longer a concept of ‘work-life balance’ but now a concept of ‘work-life integration’. We now have more tasks to squeeze into a day, without scheduled ‘on’ and ‘off’ times for each task. This integration is particularly problematic when new research has now shown that we need fully detach in order to recover.

There are four typical ways people recover from work:

Okay, so what did the research say was the best technique? Of course, the answer is “it depends”! If you experiencing fatiguing demands during your day, the best thing you can so is to detach to rejuvenate. Some examples of how to detach include turning off your work email/phone, engaging in group activities, or reading. Detaching will allow you to complete your home tasks without distraction allowing you to focus solely on work the next day. It will also allow you to sleep better at night by stopping any ruminations over tomorrow’s work day. If you facing invigorating demands, the best thing you can do is control. Scheduling your work and non-work tasks will allow you to keep control of your demands, ensuring they remain a source of energy rather than become a source of fatigue. Other suggestions on how to control your demands is to make to-do list’s and set daily, weekly, and monthly goals. Having greater control will increase your self-efficacy and allow you to feel that you accomplished more. Even though the research found these are the best techniques, it doesn’t mean ignore the other techniques. If you can, combine them! For instance, meditation will allow you to detach and relax. Using multiple techniques will have an incremental effect to reduce you fatigue. Overall, although work-life integration can increase flexibility and autonomy, we run the risk of not recovering from our demands. Ensure you schedule time to detach to avoid burnout and to remain energized at work. |

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed